Sessile drop technique

The Sessile Drop Technique is a method used for the characterization of solid surface energies, and in some cases, aspects of liquid surface energies. The main premise of the method is that by placing a droplet of liquid with a known surface energy, the shape of the drop, specifically the contact angle, and the known surface energy of the liquid are the parameters which can be used to calculate the surface energy of the solid sample. The liquid used for such experiments is referred to as the probe liquid, and the use of several different probe liquids is required.

Contents |

Probe Liquid

The surface energy is measured in units of Joules per area, which is equivalent in the case of liquids to surface tension, measured in newtons per meter. The overall surface tension/energy of a liquid can be acquired through various methods using a tensiometer or using the pendent drop technique and Maximum bubble pressure method.

The interface tension at the interface of the probe liquid and the solid surface can additionally be viewed as being the result of different types of intermolecular forces. As such, surface energies can be subdivided according to the various interactions that cause them, such as the surface energy due to dispersive (van der Waals) forces, hydrogen bonding, polar interactions, acid/base interactions, etc. It is often useful for the sessile drop technique to use liquids that are known to be incapable of some of those interactions (see table 1). For example, the surface tension of all straight alkanes is said to be entirely dispersive, and all of the other components are zero. This is algebraically useful, as it eliminates a variable in certain cases, and makes these liquids essential testing materials.

The overall surface energy, both for a solid and a liquid, is assumed traditionally to simply be the sum of the components considered. For example, the equation describing the subdivision of surface energy into the contributions of dispersive interactions and polar interactions would be:

S =

S =  SD +

SD +  SP

SP

L =

L =  LD +

LD +  LP

LP

Where  S is the total surface energy of the solid,

S is the total surface energy of the solid,  SD and

SD and  SP are respectively the dispersive and polar components of the solid surface energy,

SP are respectively the dispersive and polar components of the solid surface energy,  L is the total surface tension/surface energy of the liquid, and

L is the total surface tension/surface energy of the liquid, and  LD and

LD and  LP are respectively the dispersive and polar components of the surface tension.

LP are respectively the dispersive and polar components of the surface tension.

In addition to the tensiometer and pendant drop techniques, the sessile drop technique can be used in some cases to separate the known total surface energy of a liquid into its components. This is done by reversing the above idea with the introduction of a reference solid surface that is assumed to be incapable of polar interactions, such as Polytetrafluoroethylene (PTFE)[1].

Contact angle

The contact angle is defined as the angle made by the intersection of the liquid/solid interface and the liquid/air interface. It can be alternately described as the angle between solid sample’s surface and the tangent of the droplet’s ovate shape at the edge of the droplet. A high contact angle indicates a low solid surface energy or chemical affinity. This is also referred to as a low degree of wetting. A low contact angle indicates a high solid surface energy or chemical affinity, and a high or sometimes complete degree of wetting. For example, a contact angle of zero degrees will occur when the droplet has turned into a flat puddle; this is called complete wetting.

Measuring contact angle

Goniometer method

The simplest way of measuring the contact angle is with a goniometer, which allows the user to measure the contact angle visually. The droplet is deposited by a syringe pointed vertically down onto the sample surface, and a high resolution camera captures the image, which can then be analyzed either by eye (with a protractor) or using image analysis software. The size of the droplet can be increased gradually so that it grows proportionally, and the contact angle remains congruent. By taking pictures incrementally as the droplet grows, the user can acquire a set of data to get a good average. If necessary, the receding contact angle can also be measured by depositing a droplet via syringe and recording images of the droplet being gradually sucked back up.

Advantages and disadvantages

The advantage of this method, aside from its relatively straightforward nature, is the fact that with a large enough solid surface, multiple droplet can be deposited in various locations on the sample to determine heterogeneity. The reproducibility of particular values of the contact angle will reflect the heterogeneity of the surface’s energy properties. Conversely, the disadvantage is that if the sample is only large enough for one droplet, then it will be difficult to determine heterogeneity, or consequently to assume homogeneity. This is particularly true because conventional, commercially available goniometers do not swivel the camera/backlight set up relative to the stage, and thus can only show the contact angle at two points: the right and the left edge of the droplet. In addition to this, this measurement is hampered by its inherent subjectivity, as the placement of the lines is determined either by the user looking at the pictures or by the image analysis software’s definition of the lines.

Wilhelmy method

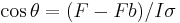

An alternative method for measuring the contact angle is the Wilhelmy method, which employs a sensitive force meter of some sort to measure a force that can be translated into a value of the contact angle. In this method, a small plate-shaped sample of the solid in question, attached to the arm of a force meter, is vertically dipped into a pool of the probe liquid (in actuality, the design of a stationary force meter would have the liquid being brought up, rather than the sample being brought down), and the force exerted on the sample by the liquid is measured by the force meter. This force is related to the contact angle by the following equation:

Where F is the total force measured by the force meter, Fb is the force of buoyancy due to the solid sample displacing the liquid, I is the wetted length, and sigma is the known surface tension of the liquid.

Advantages and disadvantages

The advantage of this method is that it is fairly objective and the measurement yields data which is inherently averaged over the wetted length. Although this does not help determine heterogeneity, it does automatically give a more accurate average value. Its disadvantages, aside from being more complicated than the goniometer method, include the fact that sample of an appropriate size must be produced with a uniform cross section in the submersion direction, and the wetted length must be measured with some precision. In addition, this method is only appropriate if both sides of the sample are identical, otherwise the measured data will be a result of two completely different interactions[2].

Strictly speaking, this is not a sessile drop technique, as we are using a small submerging pool, rather than a droplet. However, the calculations described in the following sections, which were derived for the relation of the sessile drop contact angle to the surface energy, apply just as well.

Determining Surface Energy

While surface energy is conventionally defined as the work required to build a unit of area of a given surface[3], when it comes to its measurement by the sessile drop technique, the surface energy is not quite as well defined. The values obtained through the sessile drop technique depend not only on the solid sample in question, but equally on the properties of the probe liquid being used, as well as the particular theory relating the parameters mathematically to one another.

There are numerous such theories developed by various researchers. These methods differ in several regards, such as derivation and convention, but most importantly they differ in the number of components or parameters which they are equipped to analyze. The simpler methods containing fewer components simplify the system by lumping surface energy into one number, while more rigorous methods with more components are derived to distinguish between various components of the surface energy. Again, the total surface energy of solids and liquids depends on different types of molecular interactions, such as dispersive (van der Waals), polar, and acid/base interactions, and is considered to be the sum of these independent components. Some theories account for more of these phenomena than do other theories. These distinctions are to be considered when deciding which method is appropriate for the experiment at hand. The following are a few commonly used such theories.

One component theories

The Zisman Theory

The Zisman theory is the simplest commonly used theory, as it is a one component theory, and is best used for non-polar surfaces. This means that polymer surfaces that have been subjected to heat treatment, corona treatment, plasma cleaning, or polymers that contain heteroatoms do not lend themselves to this particular theory, as they tend to be at least somewhat polar. The Zisman theory also tends to be more useful in practice for surfaces with lower energies.

The Zisman theory simply defines the surface energy as being equal to the surface energy of the highest surface energy liquid that wets the solid completely. That is to say, the droplet will disperse as much as possible, i.e. completely wetting the surface, for this liquid and any liquids with lower surface energies, but not for liquids with higher surface energies. Since this probe liquid could hypothetically be any liquid, including an imaginary liquid, the best way to determine the surface energy by the Zisman method is to acquire data points of contact angles for several probe liquids on the solid surface in question, and then plot the cosine of that angle against the known surface energy of the probe liquid. By constructing the Zisman plot, one can extrapolate the highest liquid surface energy, real or hypothetical, that would result in complete wetting of the sample with a contact angle of zero degrees.

Accuracy/precision

The line coefficient (Fig 5) suggests that this is a fairly accurate result, however this is only the case for the pairing of that particular solid with those particular liquids. In other cases, the fit may not be so great (such is the case if we replace polyethylene with poly(methyl methacrylate), wherein the line coefficient of the plot results using the same list of liquids would be significantly lower). This shortcoming is a result of the fact that the Zisman theory treats the surface energy as one single parameter, rather than accounting for the fact that, for example, polar interactions are much stronger than dispersive ones, and thus the degree to which one is happening versus the other greatly affects the necessary calculations. As such, it is a simple but not particularly robust theory. Since the premise of this procedure is to determine the hypothetical properties of a liquid, the precision of the result depends on the precision to which the surface energy values of the probe liquids are known.

Two component theories

The Owens/Wendt Theory

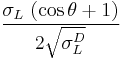

The Owens/Wendt theory (after C. J. van Oss and John F. Wendt) divides the surface energy into two components: surface energy due to dispersive interactions and surface energy due to polar interactions. This theory is derived from the combination of Young's relation, which relates the contact angle to the surface energies of the solid and liquid and to the interface tension, and Good’s equation (after R. J. Good), which relates the interface tension to the polar and dispersive components of the surface energy. The resulting principle equation is:

=

=  +

+

Note that this equation has the form of y=mx+b, with:

y =  ; m =

; m =  ; x =

; x =  ; b =

; b =

As such, the polar and dispersive components of the solid’s surface energy are determined by the slope and intercept of the resulting graph. Of course, the problem at this point is that in order to make that graph, knowing the surface energy of the probe liquid is not enough, as it is necessary to know specifically how it breaks down into its polar and dispersive components as well.

To do this, one can simply reverse the procedure by testing the probe liquid against a standard reference solid that is not capable of polar interactions, such as PTFE. If the contact angle of a sessile drop of the probe liquid is measured on a PTFE surface, the principle equation reduces to:

=

=

Since the total surface tension of the liquid is already known, this equation determines the dispersive component, and the difference between the total and dispersive components gives the polar component.

Accuracy/precision

The accuracy and precision of this method is supported largely by the confidence level of the results for appropriate liquid/solid combinations (as seen, for example, in fig 6). The Owens/Wendt theory is typically applicable to surfaces with low charge and moderate polarity. Some good examples are polymers that contain heteroatoms, such as PVC, polyurethanes, polyamides, polyesters, polyacrylates, and polycarbonates

The Fowkes Theory

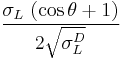

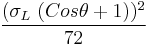

The Fowkes theory (after F. M. Fowkes) is derived in a slightly different way from the Owens/Wendt theory, although the Fowkes theory’s principle equation is mathematically equivalent to that of Owens and Wendt:

=

=  +

+

Note that by dividing both sides of the equation by  , the Owens/Wendt principle equation is recovered. As such, one of the options for the proper determination of the surface energy components is the same.

, the Owens/Wendt principle equation is recovered. As such, one of the options for the proper determination of the surface energy components is the same.

In addition to that method, it is also possible to simply do tests using liquids with no polar component to their surface energies, and then liquids that do have both polar and dispersive components, and then linearize the equations (see table 1). First, one performs the standard sessile drop contact angle measurement for the solid in question and a liquid with a polar components of zero ( =0;

=0;  =

= ) The second step is to use a second probe liquid that has both a dispersive and a polar component to its surface energy, and then solve for the unknowns algebraically. The Fowkes theory generally requires the use of only two probe liquids, as described above, and the recommended ones are diiodomethane, which should have no polar component due to its molecular symmetry, and water, which is commonly known to be a very polar liquid.

) The second step is to use a second probe liquid that has both a dispersive and a polar component to its surface energy, and then solve for the unknowns algebraically. The Fowkes theory generally requires the use of only two probe liquids, as described above, and the recommended ones are diiodomethane, which should have no polar component due to its molecular symmetry, and water, which is commonly known to be a very polar liquid.

Accuracy/precision

Though the principle equation is essentially identical to that of Owens and Wendt, the Fowkes theory in a larger sense has slightly different applications. Because it is derived from different principles than Owens/Wendt, the rest of the information that Fowkes theory is concerned with is related to adhesion. As such, it is more applicable to situations where adhesion occurs, and in general works better than does the Owens/Wendt theory when dealing with higher surface energies[1].

In addition, there is an extended Fowkes theory, rooted in the same principles, but dividing the total surface energy into a sum of three rather than two components: surface energy due to dispersive interactions, polar interactions, and hydrogen bonding[4].

The Wu Theory

The Wu theory (after Guo Xiong Wu) is also essentially similar to the Owens/Wendt and Fowkes theories, in that it divides surface energy into a polar and a dispersive component. The primary difference is that Wu uses the harmonic means rather than the geometric means of the known surface tensions, and subsequently the use of more rigorous mathematics is employed.

Accuracy/precision

The Wu theory provides more accurate results than do the other two component theories, particularly for high surface energies. It does, however, suffer from one complication: because of the mathematics involved, the Wu theory yields two results for each component, one being the true result, and one being simply a consequence of the mathematics. The challenge at this point lies in interpreting which is the true result. Sometimes this is as simple as eliminating the result that makes no physical sense (a negative surface energy) or the result that is clearly incorrect by virtue of being many orders of magnitude larger or smaller than it should be. Sometimes interpretation is more tricky.

The Schultz Theory

The Schultz theory (after D. L. Schultz) is applicable only for very high energy solids. Again, it is similar to the theories of Owens, Wendt, Fowkes, and Wu, but is designed for a situation where conventional measurement required for those theories is impossible. In the class of solids with sufficiently high surface energy, most liquids wet the surface completely with a contact angle of zero degrees, and thus no useful data can be gathered. The Schultz theory and procedure calls to deposit a sessile drop of probe liquid on the solid surface in question, but this is all done while the system is submerged in yet another liquid, rather than being done in the open air. As a result, the higher “atmospheric” pressure due to the surrounding liquid causes the probe liquid droplet to compress so that there is a measurable contact angle.

Accuracy/precision

This method is designed to be robust where the other methods don’t even provide any results in particular. As such, it is indispensable, since it is the only way to use the sessile drop technique on very high surface energy solids. Its major drawback is the fact that it is far more complex, both in its mathematics and experimentally. The Schultz theory requires one to account for many more factors, as there is now the unusual interaction of the probe liquid phase with the surrounding liquid phase. In addition, the set up of the camera and backlight become more complicated owing to the refractive properties of the surrounding liquid, not to mention the set up of the two-liquid system itself[4].

Three component theories

The van Oss Theory

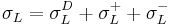

The van Oss theory separates the surface energy of solids and liquids into three components. It includes the dispersive surface energy, as before, and subdivides the polar component as being the sum of two more specific components: the surface energy due to acidic interactions ( ) and due to basic interactions (

) and due to basic interactions ( ). The acid component theoretically describes a surface’s propensity to have polar interactions with a second surface that has the ability to act basic by donating electrons. Conversely, the base component of the surface energy describes the propensity of a surface to have polar interactions with another surface that acts acidic by accepting electrons. The principle equation for this theory is:

). The acid component theoretically describes a surface’s propensity to have polar interactions with a second surface that has the ability to act basic by donating electrons. Conversely, the base component of the surface energy describes the propensity of a surface to have polar interactions with another surface that acts acidic by accepting electrons. The principle equation for this theory is:

=

= ![2[\sqrt{\sigma_L^D\sigma_S^D} %2B \sqrt{\sigma_L^-\sigma_S^%2B} %2B \sqrt{\sigma_L^%2B\sigma_S^-}]](/2012-wikipedia_en_all_nopic_01_2012/I/7710513b6fca810207b82f7193e1d6a1.png)

Again, the best way to deal with this theory, much like the two component theories, is to use at least three liquids (more can be used to get more results for statistical purposes) – one with only a dispersive component to its surface energy ( ), one with only a dispersive and an acidic or basic component (

), one with only a dispersive and an acidic or basic component ( ), and finally either a liquid with a dispersive and a basic or acidic component (whichever the second probe liquid did not have (

), and finally either a liquid with a dispersive and a basic or acidic component (whichever the second probe liquid did not have ( )), or a liquid with all three components (

)), or a liquid with all three components ( ) – and linearizing the results.

) – and linearizing the results.

Accuracy/precision

Being a three component theory, it is naturally more robust than other theories, particularly in cases where there is a great imbalance between the acid and base components of the polar surface energy. The van Oss theory is most suitable for testing the surface energies of inorganics, organometallics, and surface containing ions.

The most significant difficulty of applying the van Oss theory is the fact that there is not much of an agreement in regards to a set of reference solids that can be used to characterize the acid and base components of potential probe liquids. There are however some liquids that are generally agreed to have known dispersive/acid/base components to their surface energies. Two of them are listed in table 1.

List of common probe liquids

Table 1

| Liquid | Total Surface Tension (mN/m) | Dispersive Component (mN/m) | Polar Component (mN/m) | Acid Component (mN/m) | Base Component (mN/m) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Diiodomethane | 50.8 | 50.8 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Water | 72.8 | 26.4 | 46.4 | 23.2 | 23.2 |

Potential problems

The presence of surface active elements such as oxygen and sulfur will have a large impact on the measurements obtained with this technique. Surface active elements will exist in larger concentrations at the surface than in the bulk of the liquid, meaning that the total levels of these elements must be carefully controlled to a very low level. For example, the presence of only 50 ppm sulphur in liquid iron will reduce the surface tension by approximately 20%[5].

Practical applications

The sessile drop technique has various applications for both materials engineering and straight characterization. In general, it is useful in determining the surface tension of liquids through the use of reference solids. There are various other specific applications which can be subdivided according to which of the above theories is most likely to be applicable to the circumstances:

The Zisman theory is mostly used for low energy surfaces and characterizes only the total surface energy. As such, it is probably most useful in cases that recall the conventional definition of surfaces, for example if a chemical engineer wants to know what the energy associated with fabricating a surface is. It may also be useful in cases where the surface energy has some effect on a spectroscopic technique being used on the solid in question.

The two component theories would most likely be applicable to materials engineering questions about the practical interactions of liquids and solids. The Fowkes theory, since it is more suited for higher energy solid surfaces, and since much of it is rooted in theories about adhesion, would likely be suited for the characterization of interactions where the solids and liquids have a high affinity for one another, such as, logically enough, adhesives and adhesive coatings. The Owens/Wendt theory, which deals in low energy solid surfaces, would be helpful in characterizing the interactions where the solids and liquids do not have a strong affinity for one another – for example, the effectiveness of waterproofing. Polyurethanes and PVC are good examples of waterproof plastics.

The Schultz theory is best used for the characterization of very high energy surfaces for which the other theories are ineffective, the most significant example being bare metals.

The van Oss theory is most suitable for cases in which acid/base interaction is an important consideration. Examples include pigments, pharmaceuticals, and paper. Specifically, notable examples include both paper used for the regular purpose of printing, and the more specialized case of litmus paper, which in itself is used to characterize acidity and basicity.

See also

References

- ^ a b c Christopher Rullison, "So You Want to Measure Surface Energy?". Kruss Laboratories technical memo.

- ^ Christopher Rullison, "A Practical Comparison of Techniques Used to Measure Contact Angles for Liquids on Non-Porous Solids". Kruss Laboratories technical note #303.

- ^ Oura K, Lifshits V G, Saranin A A, Zotov A V, and Katayama M (2001). Surface Science: An Introduction. Springer-Verlag: Berlin, 233

- ^ a b "Kruss.de, "Contact angle measurement – a theoretical approach"". http://www.kruss.de/en/theory/measurements/contact-angle/introduction.html.

- ^ Seshadri Seetharaman: Fundamentals of metallurgy, Woodhead Publishing in Materials, Cambridge, 2005.